Jane Greer as Kathie Moffat in Out of the Past (1947), a typical femme fatale.

Where did this idea of dangerous women originate from? Perhaps, it came into being because it was based off of certain mens' disastrous past relationships with their lovers. Femme fatales could be the reflection of a general fear about the consequences of entering a relationship that a man knows little about, and the unfortunate effects that might come with that relationship (i.e. giving into temptation, new responsibilities, commitment, childcare). In early history, the idea of a powerful women or female ruler was rather frightening for some as it was rather unheard of. Likely, many men questioned how effective such rulers were while in power. No doubt, the femme fatale also represents humankind's paradoxical attraction and repulsion of sex.

Some of the earliest examples of femme fatales date back to genesis of literature. Aphrodite (Venus), the goddesses of love, beauty, and procreation, had numerous affairs with several other gods and often ignited jealousy among immortals and mortals alike. She caused so much trouble that Zeus had her wed Hephaestus, a cripple who was skilled at metallurgy. Even Aphrodite's birth was rather suggestive. She arose from sea foam after Cronus threw Uranus's genitals into the ocean. Aphrodite was also known for being vain and easily offended. Her personality along with her control of magic and enticement of men, would become the basis of several figures to follow.

The Birth of Venus by Sandro Botticelli (1485).

In Greek mythology, there are others that have the qualities of seductive, deadly women. Sirens (along with mermaids and nymphs) were feared for luring men into drowning by playing their lovely music, singing, or by their appearance alone. Clytemnestra, was Helen's half sister. She is infamously remembered for killing her husband, Agamemnon, after he returns from Troy, so that she can marry Aegisthus. Circe, the enchantress, briefly held Odysseus's men captive after transforming them into pigs with drug laced wine. The Sphinx, borrowed from Egyptian lore, was a female hybrid creature said to devour any man who could not solve her riddles. Hecate, was known as the goddess of crossroads, misfortune, and accidents. She would later become associated with the mysteriousness of the night and witchcraft.

Hylas and the Nymphs by John William Waterhouse (1896).

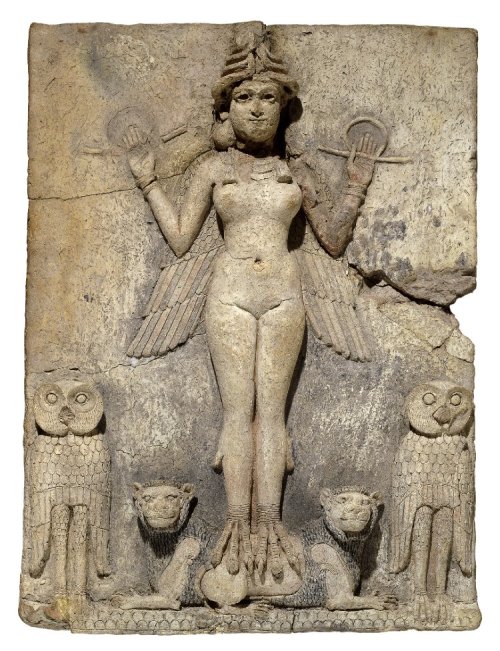

Biblical texts also mentions several femme fatale like women in its Hebrew portion. Vanity and giving into temptation or seduction are commonly considered to be crimes in many religions. Although Eve is not really a femme fatale, she certainly represented the fear of disobeying God when she committed the first sin on Earth (similar to how Pandora could not contain her curiosity and opened the box she was given, letting misfortune into the world). Lilith ('screech owl'), was a female figure based off of earlier Mesopotamian demons, and Delilah was known for betraying Sampson when she cut his hair. Also notable were Salome, who gets revenge for her mother by receiving John the Baptist's head in return for her dancing, and Jezebel, who was a Phoenician queen and 'enemy of God's prophets'.

The Burney Relief depicting Lilith (Mesopotamian origin, 1800 - 1750 BC).

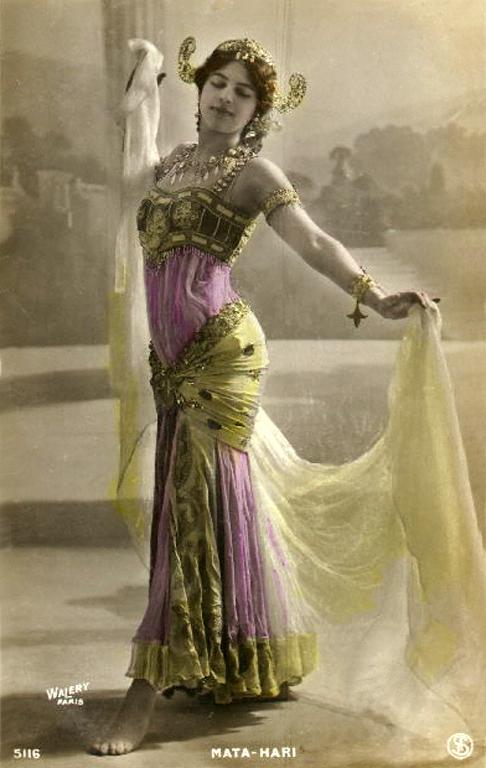

Outside of fiction and witch trails, there were several real life people who are considered to be femme fatales. Cleopatra, although much of her life in popular culture is fictionalized, is probably the most famous example. Coming from a family of Greek origin, Cleopatra ruled Egypt from approximately 69 to 30 BC. She was the last pharaoh and had affairs with powerful Roman generals Julius Cesar and Mark Antony. Mata Hari was a supposed German spy who acted as an erotic dancer and entertainer. She was executed by the French army in 1917. More recently, Anna Chapman was also accused of being a spy. She was posing as a fashion model in order to obtain information about the US for the Russian government.

Mata Hari, the world's most famous female spy.

In film, arguably the first major femme fatal figure was Theda Bara, famous for her portrayal as the 'vamp', one of cinema's earliest sex symbols. She wore many outfits that were (and still are) rather racy, perhaps in part prompting Hollywood to adopt the Hayes Box Office Code about ten years later. She is best known for starring in A Fool There Was (1915), Cleopatra (1917), and The She Devil (1918). Most of Bara's films are now lost due to many being destroyed with the implantation of The Hayes Code or burning in fires.

Louis "Lulu" Brooks was another notable silent film star. She was a fiercely outspoken and independent woman who initially started her career in Hollywood, but would later move to Germany after a falling out over the use of sound with Paramount (for The Canary Murder Case [1929]). She was a critic of the Hollywood system, popularized the bobbed hair cut, and would go to star in more complex, darker films after leaving America. Brooks had several affairs (once even with Charlie Chaplin), but was never able to achieve a stable marriage, which she attributes to being assaulted at age nine, making her leery of entering long time relationships. Her greatest films arguably were Beggars for Life (1928), Pandora's Box (1929), Diary of a Lost Girl (1929), and Prix de Beaute (1930).

Many of these silent femme fatales, such as Louis Glaum and Musidora, were foreign in appearance (specifically Eastern European or Asian) which added to their mysterious allure. Their assertive and sometimes wild behavior was also a reflection of the increasing presence of women in the 1920s outside of the domestic sphere (the flapper, women gaining the right to vote with the 19th Amendment, more women going to college, etc). These actresses were the exact opposite of the more wholesome and innocent performances of stars such as Lillian Gish or Mary Pickford.

The few remaining seconds discovered of Theda Bara as Cleopatra (1917), and an interview with Bara.

Louise Brooks was another silent film femme fatale.

In the 1940s, many German filmmakers fled their homeland to avoid censorship from the Nazi regime and brought their unique, dark, and complex expressionist style with them, forever altering America cinema. Film Noir thus came into being and its style was adopted by several famous directors, including Alferd Hitchcock and Orson Wells. It is characterized by its crime ridden plot lines commonly involving antiheroes, dramatic black and white lighting, and (surprise!) femme fatales. The goal of film noir was to challenge the Hays Code and typical, 'safer' American movies made at the time. Some of the most famous film noir films include: Rebecca (1940), Citizen Cane (1941), The Maltese Falcon (1941), Laura (1944), The Big Sleep (1946), Gilda (1946), Out of the Past (1947), Vertigo (1958), and Psycho (1960). Sunset Blvd (1950) was particularly interesting. It cast Gloria Swanson as Norma Desmond, an eccentric former silent film star, obsessed with rising back to fame and her ill fated relationship with the young screenwriter Joe Gillis (William Holden).

"All right Mr. DeMillie, I'm ready for my closeup."

To this day, there are many films that follow the pattern of femme fatales found in film noir. Some recent examples of 'neo-noir' fatales include the likes of Evelyn Mulwray from Chinatown (1974), Matty Walker of Body Heat (1981), Alex Forrest from Fatal Attraction (1987), Lynn Bracken from L.A. Confidential (1997), and Mal Cobb from Inception (2010). A notable example of the femme fatale is the 'Bond Girl.' A Bond Girl is any of the classy, outspoken women from the James Bond film series. They are known for their often sexually suggestive names, troubled pasts, and penchant for betrayal. Femme fatales are common outside of American cinema as well, perhaps the best know being the anime characters Fujiko Mime from the Lupin the Third franchise and Fey from Cowboy Bebop (1998).

Parodies of the femme fatale have also been popular ever since the 1940s. Animator Tex Avery gave as Red Hot Riding (1943) which mocked traditional fairytale conventions by updating them for modern audiences. Eartha Kitt's enjoyably campy performance for the third season original Batman show (1967 - 1968), was laced with puns and hamminess. Jessica Rabbit from Who Framed Roger Rabbit? (1988) makes a tongue in cheek reference to the archetype stating, "I'm not bad. I'm just drawn that way." Kiss Kiss Bang Bang (2005) poked fun at noir conventions with its twisted black humor and plot about a thief being mistaken for an actor and detective.

Parodying the femme fatale: Eirtha Kitt as Catwoman!

Fujiko Mime, anime's answer to the fatale archetype.

Whether you agree with the implications of the character role or not, the femme fatale is here to stay and has long been part of our cultural heritage and imagination. She can be seen as a threat to traditional gender roles, a sexually liberated individual, or a manipulative honey trap. Depending on the context, this woman archetype is commonly seen as a cool, confident woman or nuisance to beware of. In either case, the femme fatale is one of the most recognizable figures conceived for fiction.

No comments:

Post a Comment